Part 1 and Part 2 covered the theory and one major commercial platform. Now the practical question: what does the open-source Kubernetes ecosystem actually give you for intelligent autoscaling in 2024, and where is the ML layer starting to plug in? The answer is more composable — and more interesting — than it was two years ago.

There's a tendency to think about autoscaling as a single dial: turn it up, get more pods. The reality in a modern Kubernetes environment is that autoscaling is actually a set of nested loops operating at different time scales and different layers of the stack. Untangling those loops — and understanding which open tools own which layer — is the point of this post.

Three Tools, Three Distinct Jobs

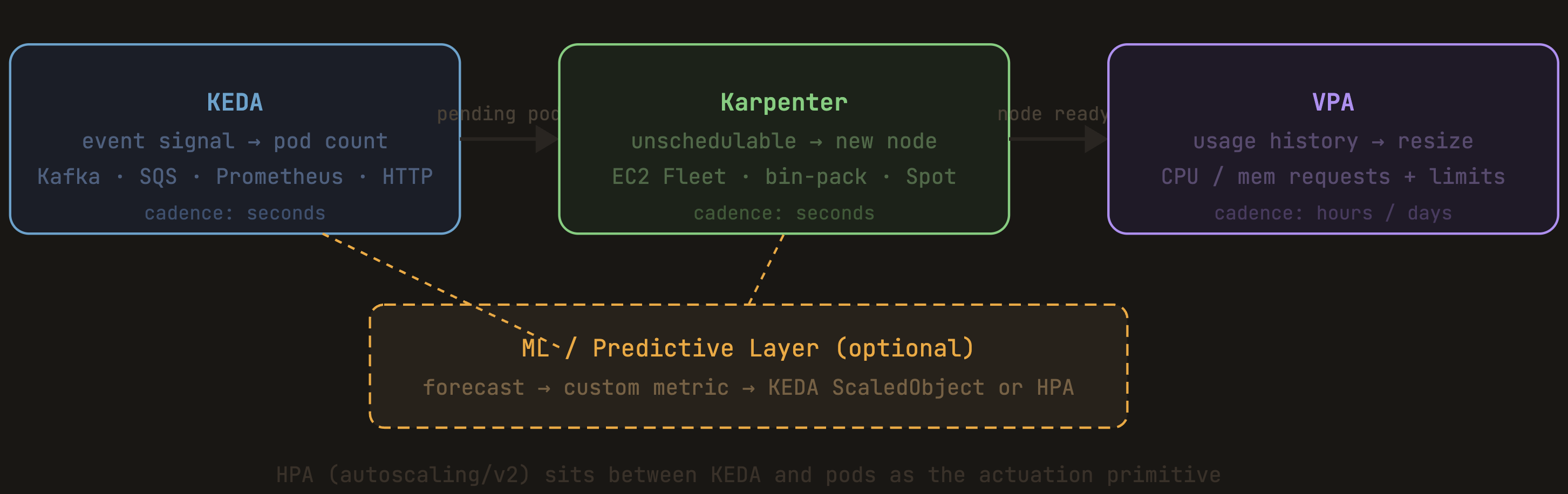

By early 2024, the CNCF ecosystem has essentially converged on three core primitives for autoscaling. They're complementary, not competing:

KEDA (Pod Layer · CNCF Graduated) Event-driven pod scaling. 50+ scalers out of the box — Kafka lag, SQS depth, Prometheus queries, HTTP concurrency. Critically: enables true scale-to-zero. Works as an HPA controller replacement or alongside it.

Karpenter (Node Layer · AWS / CNCF) Groupless node provisioning via EC2 Fleet API. Provisions in seconds, not minutes. Bin-packs, consolidates, handles Spot interruptions. Replaces Cluster Autoscaler for teams on AWS that need speed and flexibility.

VPA (Resource Sizing · Kubernetes SIG) Right-sizes CPU and memory requests per container based on observed usage. Runs well in recommendation mode — feeds sizing hints to operators or CI pipelines without requiring disruptive in-place restarts.

The key insight is that KEDA and Karpenter compose into a two-tier loop: KEDA decides how many pods you need based on upstream demand signals, Karpenter makes sure the nodes exist to schedule them, instantly. Before Karpenter, you were waiting 3–5 minutes for a new node to join the cluster. That latency made predictive scaling almost mandatory for any latency-sensitive workload. Karpenter shifts node provisioning from a constraint to almost a non-issue.

Where the ML Layer Plugs In

KEDA graduated as a CNCF project in 2023, which matters because graduation signals production readiness and API stability. But what makes it particularly interesting from an ML perspective is a subtle architectural feature: it extends HPA, which means anything you can express as a metric, KEDA can scale on.

That's the hook for predictive autoscaling. The pattern looks like this: you run a forecasting model (Prophet, LSTM, whatever fits your workload) that publishes a short-horizon demand prediction as a Prometheus metric. You configure KEDA's Prometheus scaler — or use the Prometheus Adapter to surface it to HPA — and the autoscaler responds to your predicted demand rather than observed CPU. The underlying K8s plumbing stays entirely standard.

KEDA also ships a PredictKube scaler, which wires directly to a Dysnix-maintained ML SaaS for AI-based predictive scaling from Prometheus metrics. It's the only truly native "ML-first" scaler in the ecosystem right now. Whether you want a SaaS dependency in that loop is a legitimate question, but it at least proves the integration pattern works cleanly.

The scrape lag problem is real. With Prometheus scraping once per minute and HPA syncing every 15 seconds, you can be 30–90 seconds late to a 20-second spike — and p95 slips while average CPU looks fine. Pushing a forecast metric rather than pulling observed utilization is one direct fix. KEDA's HTTP scaler, which reacts to in-flight request concurrency rather than scraped metrics, is another.

What the Research Says (Without Overstating It)

The academic literature on SLO-driven and ML-native autoscaling is rich, but there's an honest gap between paper results and production deployments. A few threads worth tracking:

MAPE-K based SLO autoscalers — the Monitor-Analyze-Plan-Execute loop — have been studied extensively as an alternative to pure threshold-based scaling. Recent work (2023–2024) implements this in Kubernetes against the Sock Shop benchmark and shows materially better SLO adherence than stock HPA, with both horizontal and vertical scaling handled in the same loop. The self-adaptive architecture is clean; the open question is operational complexity at scale.

RL as an outer loop around HPA is the most promising near-term research direction for ML-native scaling. The practical formulation: RL doesn't replace HPA, it learns the right target utilization threshold for HPA to track — effectively turning a static policy knob into a learned one. The reward signal is straightforward: SLO penalty + cost + stability. The hard part is safe exploration and preventing the RL agent from doing something expensive during training. Off-policy learning from historical logs before any live deployment is now fairly standard practice in this space.

Hybrid Prophet + LSTM for Kubernetes workload forecasting has shown good results in 2023–2024 research: Prophet handles the seasonal decomposition (daily/weekly cycles), LSTM fits the residuals. The combined model outperforms either alone on real cluster traces. This is the academic refinement of the forecasting approach I described in Part 1.

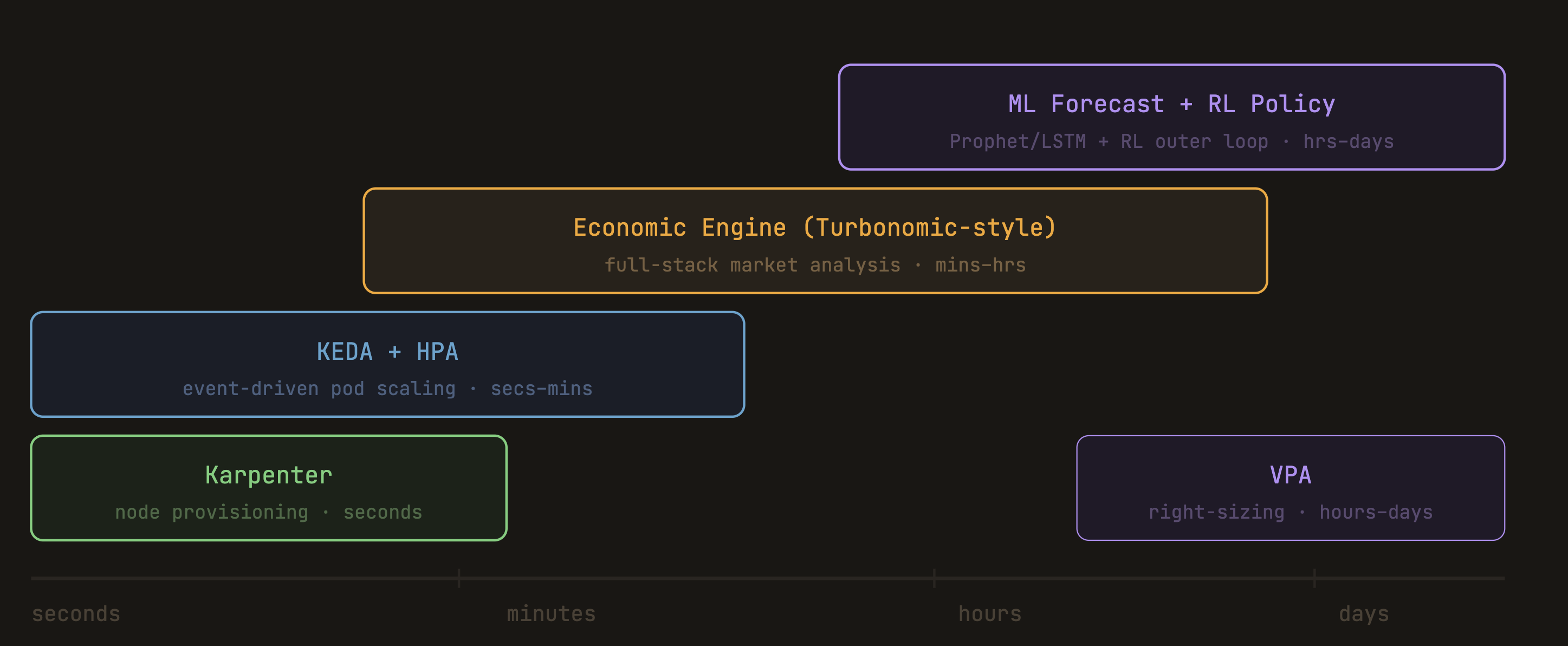

The Synthesis: What a Complete Stack Looks Like

Pulling together all three posts — theory, Turbonomic's commercial model, and the open-source ecosystem — here's how a complete, ML-informed autoscaling stack fits together by mid-2024:

Node Layer: Karpenter Fast, groupless node provisioning — eliminates boot time as the main argument for heavy predictive investment

Pod Layer: KEDA + HPA v2 Event-driven scaling on any signal, scale-to-zero, stable API to publish custom/forecast metrics into

Sizing Layer: VPA (recommend mode) Right-sizes resource requests over time; feeds CI pipelines or kubeturbo-style automation

Stack Layer: Economic engine (Turbonomic) Holistic cross-layer market analysis; best for heterogeneous hybrid infra with VMs, storage, multi-cloud

Forecast Layer: Prophet / LSTM → Prometheus metric Predictive demand signal published as a custom metric; consumed by KEDA or HPA. Best for cyclical workloads

Policy Layer: RL outer loop Learns optimal target thresholds for HPA; shadow-mode first, then canary. Research-proven, production-early

You don't deploy all of these at once. The practical entry point is still KEDA + Karpenter — they solve the most common pain with the least operational overhead. The ML forecast layer adds value when you have cyclical load patterns and can invest in the metrics pipeline. The RL layer is for teams with enough traffic to generate a reward signal and enough operational maturity to run it safely alongside production.

The honest state of the field in mid-2024: the open-source primitives are excellent and composable. The ML integration layer exists and works, but you still have to build most of it yourself. Turnkey ML-native autoscaling that doesn't require a commercial platform remains the gap.

Where This Series Lands

Three posts, one thread: reactive scaling has real limits; economic models like Turbonomic solve the holistic stack problem but not the predictive one; and the open-source ecosystem is now composable enough to assemble a serious ML-informed stack without a commercial dependency — if you're willing to do the integration work.

The next frontier — not quite here yet as of this writing — is tighter feedback loops between the forecast layer and the economic engine. Right now they're mostly separate. Imagine a system where the market model knows what the demand forecast says and pre-positions resources accordingly, not reactively but speculatively. That's the missing piece, and it's where I expect the most interesting work to appear over the next couple of years.

Thanks for following along. All three posts are anchored to what was real and available before mid-2024 — no retrospective attribution, no "what we know now." If you're doing interesting things in this space, I'd genuinely like to hear about it.

This concludes the three part series. All opinions are my own.